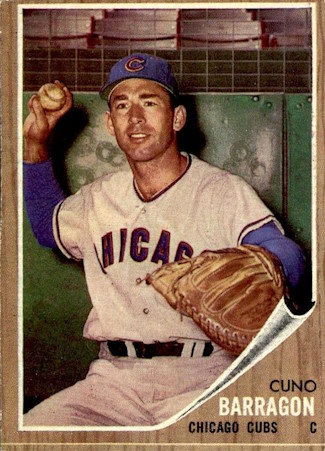

In the wide world of baseball, there are hundreds of ballplayers who never quite left their mark on a national level but are beloved in their hometown or adopted home. Such is the case of Cuno Barragan, whose major-league career amounted to 69 games with the Chicago Cubs between 1961-63. But in Sacramento, CA, he was an icon, and one of the last links to the city’s baseball past. Barragan died on May 12 at the age of 91. His wife, Karla, and The Sacramento Bee reported that he died from a combination of old age, heart failure and dementia. According to the paper, Barragan’s death means that there is just one living hometown ballplayer, Sam Kanelos, who played for the original Sacramento Solons during its existence from 1935-1960.

Facundo Anthony Barragan was born in Sacramento on June 20, 1932. He grew up as one of six children to Mexican immigrants. His father, Claudio, died from illness when Cuno was 2, and his mother Josefa died when he was 15. “When we lost our mother, we took care of ourselves,” he told the Bee in a 2016 interview. He discovered baseball at an early age and sometimes snuck into Edmonds Field, home of the Pacific Coast League’s Solons, to watch the games. He played baseball, both for Sacramento High School and for amateur summer teams, but he was far from a star player. Barragan then attended Sacramento Junior College and found success as a linebacker on the football team and a catcher on the baseball team. He was named the MVP of the football team in 1951, in fact. Pacific Coast League teams began scouting him, and the San Francisco Seals courted him, but the Sacramento Solons signed Barragan to a contract in November 1952. The 20-year-old graduated from college in January 1953 and started his career that spring.

When Barragan signed, the Sacramento Union reported that, “Cuno is a skilled receiver and has the potential to make good in the Coast League overnight, if he demonstrates the ability to hit PCL pitching.” The Solons had a tendency to sign local players, but it was decided that the young catcher needed some extra seasoning. He spent 1953 playing for the Idaho Falls Russets of the Class-C Pioneer League. In 67 games, he batted .269 with 27 RBIs, and he reached base at a .406 rate. Barragan also missed time with a concussion and fractured cheekbone after a collision with Russets first baseman/manager Red Jessen. It wasn’t the first time that injuries would impact Barragan’s career. He was unable to follow up on his solid rookie season, because he was called to serve in the U.S. Navy. He was able to play baseball on Naval teams, and he apparently was allowed to play for local amateur teams in the winter, but he did not get back to professional baseball until 1956. He was assigned to the Amarillo Gold Sox of the Western League and batted .257. Barragan also hit 20 doubles and 10 home runs while maintaining an above-.400 on-base percentage. The Solons decided to keep him on the team for 1957, but Barragan struggled against the pitching of the PCL. He was the backup to starting catcher Jim Mangan but got into 108 games, batting just .193.

For the next three years, Barragan pounced around the PCL, playing for Portland, Sacramento, Spokane and then back to Portland. In two of those transactions, he told the Bee, he was sold for a dollar. “I always thought I was worth at least $5,” he joked. Not only was he sold for a dollar twice, but it was the same dollar! Sacramento tried to assign Barragan to the Atlanta Crackers in 1958 and then suspended him when he refused to report. Portland purchased his contract for a buck, played him in 6 games, and sold him to the Solons for a dollar after he refused an assignment away from the West Coast. Sacramento then then tried to send him back to Amarillo, but he didn’t play there, either, so the sum total of the 1958 season was those 6 games for Portland. Barragan started 1959 with Sacramento but didn’t play much behind starting catcher was Clay Dalrymple. He was sent to Spokane in mid-season and ended up batting .205 between the two teams. Barragan remained with one team, Sacramento, for 1960 and split time behind the plate with Bob Roselli and J.W. Porter. In 80 games and 254 plate appearances, Barragan batted .318 and drove in 27 runs. Furthermore, he threw out 24 base-stealers and led all PCL catchers with 12 double plays. In November 1960, the Chicago Cubs took the catcher in the annual minor league draft, paying $25,000 to the Solons in return.

The 1961 Cubs were in need of a starting catcher, and Barragan looked like he could fill the role. He had been known as a good fielding catcher, but his hitting had caught up to his defense. Now 28 years old, he had a couple of reasons for his success. “I learned to be more at ease at the plate, not struggling for the hit and trying to hit the ball out of the park. Also I began to hit to the opposite field,” he told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. “That took me a long time to learn, but now I have my chance.”

Just days before the season was to begin, the Cubs were playing a spring training against Cleveland. Barragan doubled in the third inning and advanced to third base on a sacrifice bunt. As he slid into the base, his spikes caught in the dirt, and he broke his ankle. In his absence, Dick Bertell and Sammy Taylor did the bulk of the catching duties. Barragan was expected to miss the entire season, but he came back in September and played in 10 games. His major-league debut came on September 1 against the San Francisco Giants. In the bottom of the third inning, the Cubs’ Andre Rodgers hit a 2-run home run off Giants starter Dick LeMay. Barragan followed him and, in his first major-league at-bat, hit a homer of his own. He became the first player to homer in his first-ever at-bat since Frank Ernaga of the Cubs in 1957. Barragan played in 9 more games before the season ended and had 6 hits in 28 at-bats for a .214 batting average.

Barragan had a fan in El Tappe, who was part of the Cubs’ College of Coaches. Tappe envisioned Barragan and Taylor as the Cubs’ catching platoon for 1962. “Barragan was doing a wonderful job of catching, throwing, running and even hitting in spring training last year, before he was hurt,” Tappe said. While Tappe “managed” the majority of the Cub games in 1961, Charlie Metro and Lou Klein both led the Cubs more often in 1962. Bertell was once again the primary catcher, even if military service only left him able to join the team during weekend furloughs. Barragan and Moe Thacker also saw a fair share of work behind the plate. Even Tappe, at 35 years old, was activated to serve as a catcher. Barragan appeared in 58 games, including 41 starts. He slashed .201/.306/.261. He drove in 12 runs, scored 11 times, and hit 6 doubles and a triple in his 27 hits. He wasn’t satisfied with the season, per the Sacramento Union. “Fifty-eight games isn’t enough. Not playing more often hurt my hitting. A few more hits would have given me a respectable average, around .240,” he said. “I started off with something like one hit in 20 times up but later had a streak in which I played seven straight games and had 11 for 22. But one night in Philadelphia a foul tip hit my hand and I couldn’t grip the bat very well. I was out for three or four weeks.”

Barragan’s assessment of his season was pretty accurate. He was the Cubs Opening Day catcher on April 10 and had a single in 3 at-bats against Bobby Shantz — one of 5 hits Shantz allowed in a 10-2 win. Then the catcher didn’t get another hit for the month of April and ended the month with an .063 batting average. The best stretch of his season came from May 11-18. In that 8-day stretch, Barragan had 11 hits for a .407 batting average, including 3 doubles The only game in which he did not hit safety was the second game of a doubleheader on May 13 against the Phillies, after getting 2 hits in the first game. He made periodic starts throughout the rest of the season, but he never had such a productive stretch again. He was a part of the Cubs’ 1963 Opening Day roster after spending spring training trying to learn how to switch-hit, but he made just one appearance, on April 21. He substituted for Bertell in the seventh inning of a game against the Giants and struck out in his only at-bat against Jim Duffalo. It was his final at-bat in the major leagues, as Chicago sent him to Triple-A Sale Lake City when the rosters contracted. Barragan batted .284 with 3 homers and was traded to Los Angeles in the offseason in a move that also sent Jim Brewer to the Dodgers for Dick Scott. He and the Dodgers’ Triple-A affiliate in Spokane couldn’t agree on a contract, and Barragan had an interest in getting into the life insurance business. Ultimately, he elected to return home to Sacramento and retire from baseball at the age of 31.

Over the 3 seasons with the Cubs, Barragan appeared in 69 games and slashed .202/.298/.270. He had 6 doubles, 1 triple and 1 home run. He drove in 14 runs and scored 14 times. During his 7-year minor-league career, Barragan batted .258 with 20 home runs.

After his playing career, Barragan remained an active part of Sacramento’s baseball community, particularly in the Mexican-American baseball community. He was a player/manager for teams in the County League, which is where he played as a youth. He served as an officer in the Mexican-American Baseball League and was a regular speaker at banquets around the city. When a little leaguer was injured in a power mower accident, Barragan contacted one of his former Solons teammates, Claude Raymond of the Atlanta Braves, and got the youngster an autographed Braves baseball. All the while, he continued selling life insurance and reached the “Million-Dollar Round Table” in 1970 with Cal-Western Life.

Barragan’s refusal to move around may have burned some bridges in the Pacific Coast League, but he had his reasons. “Hey, I was 29 when the Cubs signed me, and I wasn’t about to get moved all over the place in the minors,” he told the Bee in 1998. His decision to retire was based on similar principles. “I was not happy playing baseball, I was disenchanted,” Barragan said. “I had just gotten out of a bad situation in Chicago where the owner, Phil Wrigley, had a brilliant idea to not have a manager. He used a 12-man coaching staff instead. He’d rotate the coaches every once in a while, which meant that every new guy had a different philosophy, a different attitude. I got lost in the shuffle. Then the Dodgers wanted to send me down without a chance to prove myself with their club.”

Barragan also had a couple of other jobs with the Cubs that weren’t discussed until years later. The Cubs slugging third baseman, Ron Santo, had a secret that he kept from almost everyone — that he had diabetes. He was too afraid to tell the team, because he was afraid the disclosure would end his career. The only person in baseball he told was his roommate, Barragan. “He became another set of eyes for me,” Santo said. The other job, which he only disclosed in a 2016 interview with the Bee, was as a spy. While he was injured in 1962 with a broken ankle, Barragan was stationed in the Wrigley Field scoreboard with a telescope and watched the pitches that were called by the catcher. If a fastball was coming, he would turn on an exit sign by the center field wall. “One time, our guys weren’t hitting, and I asked what the problem was, and someone said a paper bag had been placed over the light,” Barragan said. “I don’t want people to think the Cubs were the only ones who did this. Everyone did it. All the players who came to the Cubs from other teams said they did the same thing.”

Zak Ford is an author who wrote Called Up, a series of stories from ballplayers relating their first trip to the majors. He interviewed Barragan before his illness, and he related Barragan’s own called-up story in this Facebook post.

Follow me on Instagram: @rip_mlb

Follow me on Facebook: ripbaseball

Follow me on Bluesky: @ripmlb

Follow me on Threads: @rip_mlb

Follow me on X: @rip_mlb

Support RIP Baseball

One thought on “Obituary: Cuno Barragan (1932-2024)”